Fossil Discovery in Venezuela Uncovers Prehistoric Sea Cow Preyed Upon by Both Crocodile and Shark

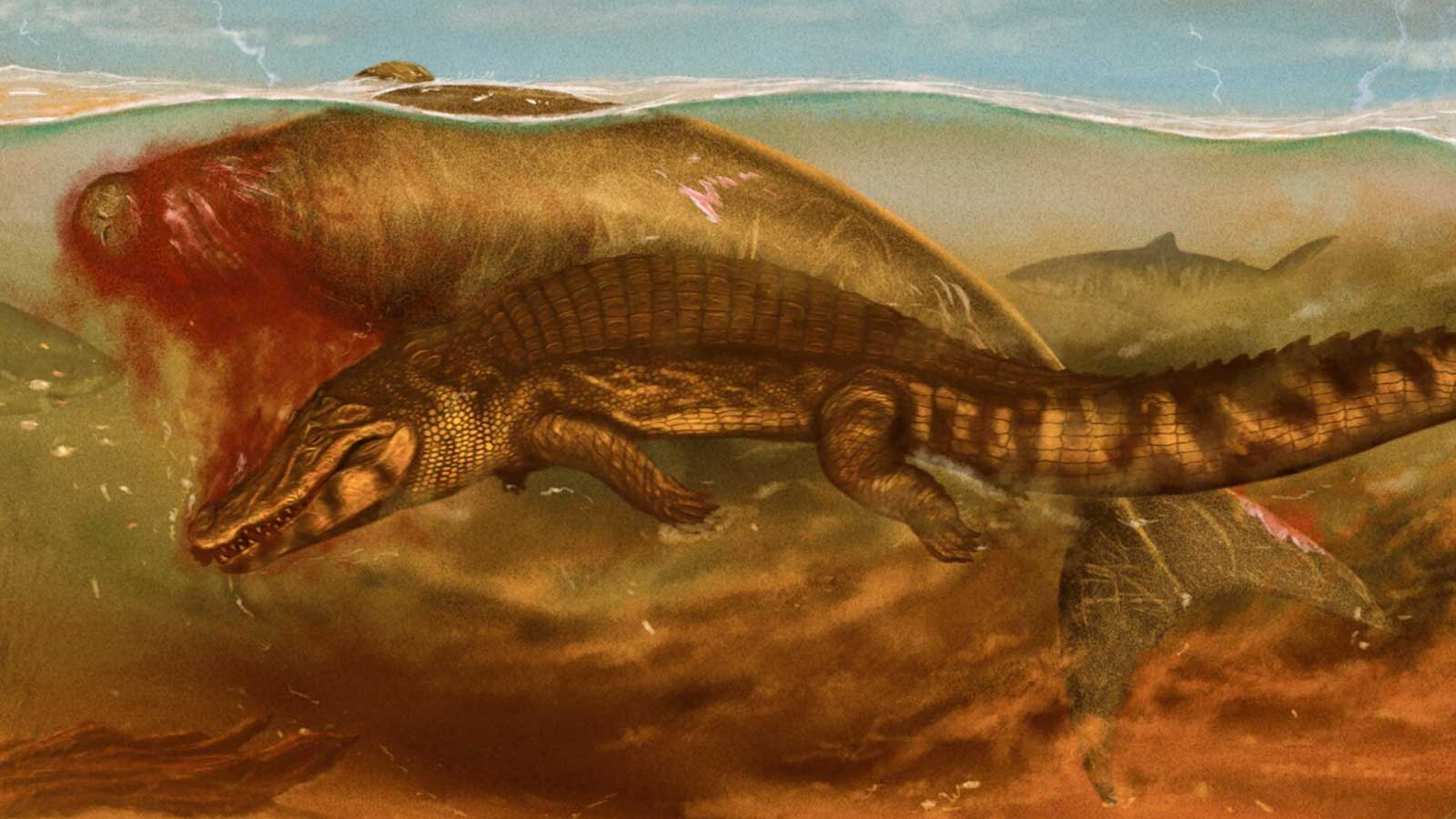

A rare fossil unearthed in Venezuela has revealed a prehistoric sea cow’s grim demise at the jaws of both a crocodile and a tiger shark approximately 15 million years ago. The fossil, belonging to an extinct species of dugong known as Culebratherium, provides a rare glimpse into a violent episode from the Miocene Epoch when this manatee-like marine mammal was attacked by two apex predators.

Scientists analyzed the fossil—a partial skull and 13 vertebrae—and identified evidence of a coordinated attack from both predators. The crocodile, likely a large species measuring between 13 and 20 feet long, appears to have struck first, leaving deep bite marks on the sea cow’s snout, likely in an attempt to suffocate it. Other large incisions suggest that the crocodile dragged the animal during a vicious “death roll,” a behavior seen in modern crocodiles that helps to subdue prey.

The sea cow’s ordeal, however, did not end with the crocodile. After the initial attack, a tiger shark—identified by the discovery of a fossilized tooth lodged in the sea cow’s neck—joined in, scavenging the remains. According to researchers, the bite marks found throughout the sea cow’s body, combined with their irregular distribution and varying depth, suggest that the tiger shark was primarily feeding on the leftovers from the crocodile’s assault.

Aldo Benites-Palomino, the study’s lead author and a doctoral student at the University of Zurich, remarked that finding evidence of two predators on a single specimen is extremely rare and offers invaluable insights into the dynamics of prehistoric food chains. The study, published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, sheds light on the interactions of marine predators and prey during the Miocene Epoch, roughly 11.6 to 23 million years ago.

Despite the compelling findings, determining whether the sea cow was actively hunted by both predators or scavenged postmortem remains a challenge. Dean Lomax, a paleontologist from the University of Bristol who was not involved in the study, pointed out that without direct evidence, it is difficult to say with absolute certainty whether the dugong was alive during both attacks. He noted that it is possible the sea cow had already died and was later scavenged by the two predators.

The fossil discovery came about by chance when a farmer in southern Venezuela stumbled upon the remains in an area not previously known for fossils. Initially, the research team struggled to identify the fossils but eventually recognized them as belonging to a dugong, an ancestor of today’s manatees and dugongs, which can grow up to 16 feet in length.

Today, dugongs and manatees are still preyed upon by sharks and crocodiles, but their size makes them less vulnerable to attacks compared to their prehistoric ancestors. The rare fossil underscores the significance of conducting paleontological research in underexplored regions like South America, where new fossil sites can provide fresh insights into ancient ecosystems.

The research team believes this discovery highlights the need to continue searching for fossils in non-traditional areas such as Venezuela, where the untapped fossil record could hold many more secrets of prehistoric life. As Benites-Palomino expressed, “We have been going to the same fossil sites in North America and China for a long time, but every time we work in these new areas, we constantly find new fossils.”