Revealing the Ritual: Insights from Translated Edo Period Texts on Samurai Beheading

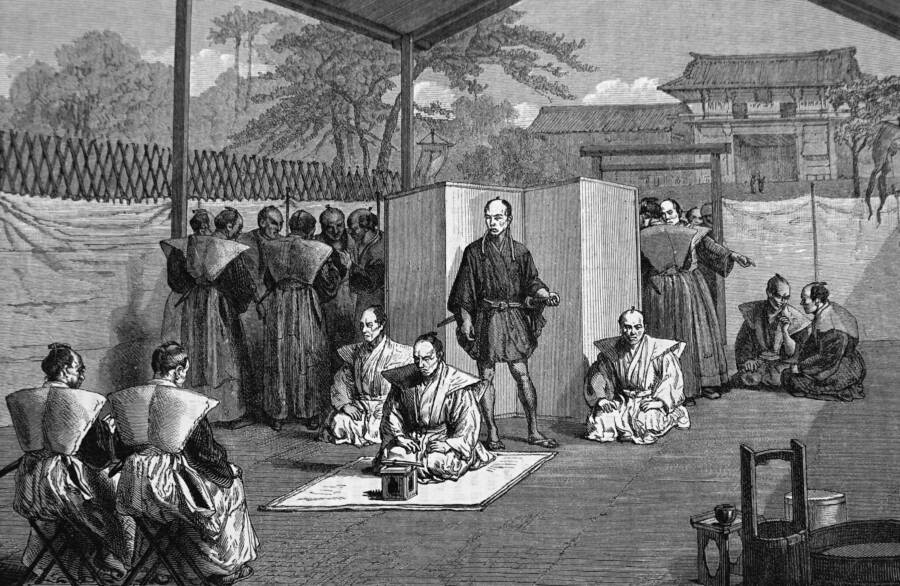

Recent translations of four significant Japanese texts offer profound insights into the ritual of samurai beheading during the Edo period (1603 to 1868). These texts challenge the widespread belief that samurai predominantly chose self-inflicted wounds as a means of honorable death. Instead, they reveal that beheading by a fellow samurai, known as kaishaku, was the more prevalent practice, highlighting the complex social and cultural dynamics surrounding this ritual. This perspective not only recontextualizes our understanding of samurai honor but also emphasizes the ceremonial importance attributed to death within the samurai code.

One of the most notable texts, The Inner Secrets of Seppuku, dates back to the 17th century and offers a wealth of teachings traditionally conveyed through oral traditions. Authored by Mizushima Yukinari, this work serves as a guide for samurai to ensure they are well-prepared for the solemnity of their fate. Eric Shahan, a scholar specializing in martial arts texts and a practitioner of Kobudo, has translated these teachings, making them accessible to modern audiences. The emphasis placed on preparation underscores the samurai’s duty to approach their end with dignity, illustrating the intricate relationship between life, death, and honor in samurai culture.

The translated texts also reveal that the ceremonial aspects of execution varied significantly based on the condemned’s rank. High-ranking samurai were afforded elaborate rituals that included the offering of sake before the execution. This ceremonial treatment not only served to honor the individual but also reinforced the hierarchical nature of samurai society. The role of the kaishaku, or designated second, was critical in these ceremonies, as they were tasked with swiftly beheading the condemned after presenting a knife, ensuring a quick and honorable death. This differentiation in rituals based on rank reflects the nuanced social structures within the samurai class and their customs regarding life and death.

Furthermore, one key instruction from the texts highlights the psychological aspects of the ritual, advising the kaishaku to focus on the eyes and feet of the condemned to maintain their martial composure. This guidance emphasizes the importance of mental fortitude and control, both for the kaishaku and the condemned, during such a harrowing moment. By studying these texts, we gain not only a clearer understanding of the samurai’s perspective on death but also insights into the broader cultural and philosophical underpinnings that shaped their actions. The newly translated texts enrich our understanding of samurai practices and invite a deeper exploration of the complexities surrounding honor, duty, and mortality in Edo-period Japan.