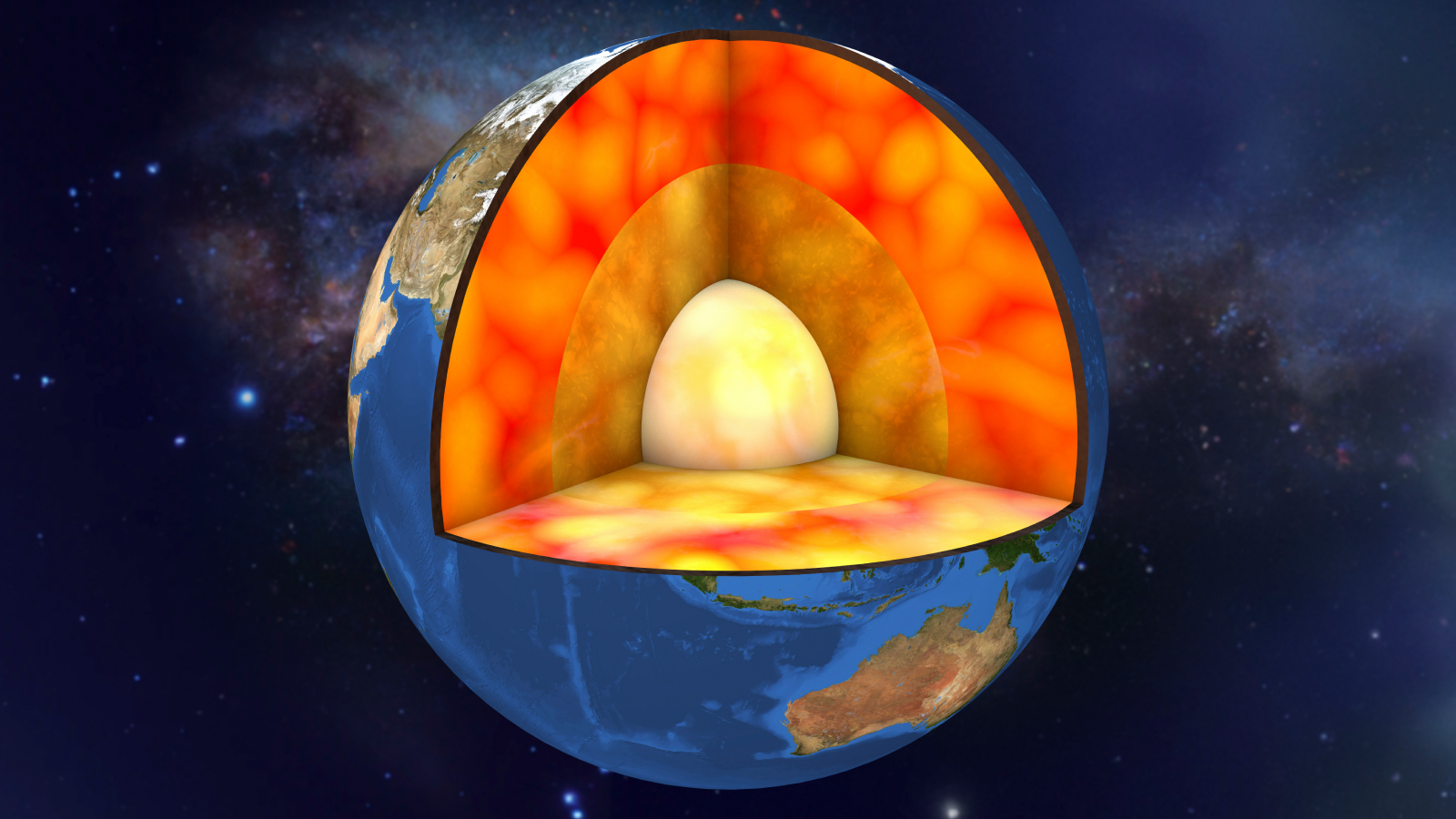

Massive continent-sized structures buried deep within Earth’s mantle may be more than a billion years old, shedding new light on the planet’s internal dynamics. Known as large low-seismic-velocity provinces (LLSVPs), these formations are distinct from the surrounding mantle due to their unique physical and chemical properties. Located at the boundary between the mantle and the outer core, roughly 3,000 kilometers beneath the surface, these enigmatic structures have intrigued scientists for decades. Their ability to slow down seismic waves suggests they are compositionally different, possibly containing denser or hotter materials than the rest of the mantle.

A recent study published in Nature analyzed seismic data from over 100 significant earthquakes to investigate these deep-mantle structures. As reported by Space.com, Utrecht University seismologist Arwen Deuss explained that while it was well known that seismic waves slow down in these regions, an unexpected finding was that the waves also lose less energy than anticipated. This suggests that temperature alone cannot account for the properties of LLSVPs, indicating that other factors—such as mineral composition or internal structure—play a role in their formation and persistence over geological time.

One of the key insights from the study is the role of crystal size in influencing how seismic waves behave within LLSVPs. Computer simulations suggest that seismic energy is affected by the grain boundaries between crystals, with smaller crystals leading to greater energy loss and larger crystals allowing waves to pass with less resistance. Deuss noted that while the surrounding mantle consists of fragmented tectonic plates that have broken down over time, the LLSVPs appear to have remained relatively undisturbed, preserving their larger crystal structures for over a billion years.

These findings offer a new perspective on the deep interior of Earth and its geological evolution. Understanding LLSVPs is crucial for unraveling the processes that shape mantle convection, plate tectonics, and even volcanic activity at the surface. Further research into these massive formations could help explain the role they have played in Earth’s history, including their potential connection to supercontinent cycles and deep-mantle plumes that drive hotspot volcanism.