Recent research indicates that Alice Molland, long recognized as the last woman hanged for witchcraft in England in 1685, may have actually escaped execution and lived for several more years. Up to 60,000 alleged witches were executed across Europe during the 1600s and 1700s, with countless others put on trial.

The Discovery

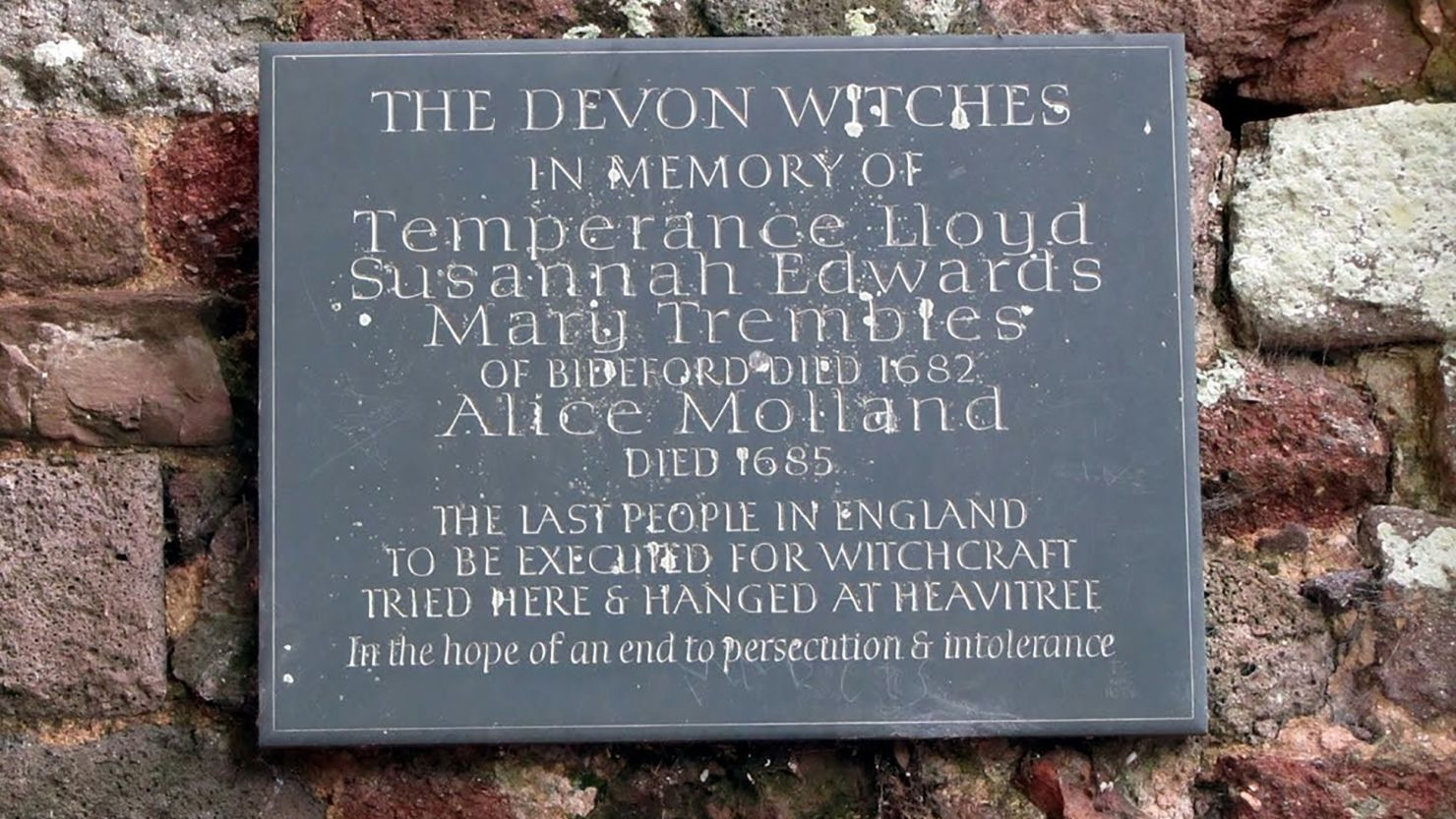

Historian Mark Stoyle from the University of Southampton has spent a decade sifting through archives, suggesting that the woman convicted might have been Avis Molland instead of Alice. If Stoyle’s hypothesis is correct, it would mean that England ceased executing witches three years earlier than previously thought, shifting the record to the Bideford Three—Temperance Lloyd, Mary Trembles, and Susannah Edwards—who were executed in 1682.

Court records show that Alice was condemned for “witchcraft on the bodyes of Joane Snell, Wilmott Snell and Agnes Furze” in March 1685. The only evidence of her conviction was her death sentence, marked with a wheel symbol and the word “susp[enditur].” Stoyle argues that a clerical error might have led to the confusion in names, and a 2013 discovery revealed a reference to Avis Molland, suggesting she was imprisoned just months after Alice’s sentencing.

The Life of Avis Molland

Born Avis Macey, Avis was part of Exeter’s underclass and had already faced legal troubles. In 1667, she and her husband were charged with encouraging a child to steal tobacco, although the case was dismissed. After becoming a widow, Avis surfaced in court records in June 1685, providing information about potential rebellion during the Duke of Monmouth’s uprising. Stoyle speculates that as the prison filled with political detainees, she may have been spared from execution.

Records indicate that Avis lived for another eight years, passing away and being buried in St. David’s church cemetery in Exeter.

Witch Hunts and Their Impact

The witch hunts of this era primarily targeted women who were perceived as different, often the elderly, single, or disabled. Stoyle notes that these accusations were rooted in societal paranoia, particularly against Catholics during the reign of Henry VIII and Elizabeth I. Historians estimate that at least 500 witches were executed in England from 1542 to 1735, with some estimates suggesting the number could be as high as 1,000.

In a broader context, these trials were prevalent not just in England but also in Scotland, which executed around 2,500 witches, and North America, most famously during the Salem witch trials, where 19 were executed.

Recognition and Justice

Campaigns for justice for the victims of these witch trials are ongoing. Charlotte Meredith, from the advocacy group Justice for Witches, argues that victims deserve posthumous pardons to acknowledge the miscarriages of justice they faced. John Worland, a retired police inspector, has dedicated years to uncovering the stories of those executed for witchcraft, particularly in Essex, where 82 were executed.

Stoyle plans to publish his findings in the upcoming issue of The Historian and reflects on the importance of bringing Avis Molland’s story to light, asserting that even if he is wrong about the connection to Alice, the work has revived awareness of her plight.

Diverging Opinions

However, some remain skeptical of Stoyle’s findings. Judy Molland, who played a pivotal role in erecting a plaque to commemorate the four Devon women executed for witchcraft, firmly believes in the existence of Alice. Despite the compelling research, she contends that there must have been a woman named Alice who faced accusations of witchcraft, illustrating the broader narrative of the countless women unjustly persecuted during this dark chapter in history.