Unveiling the Sun’s Secrets

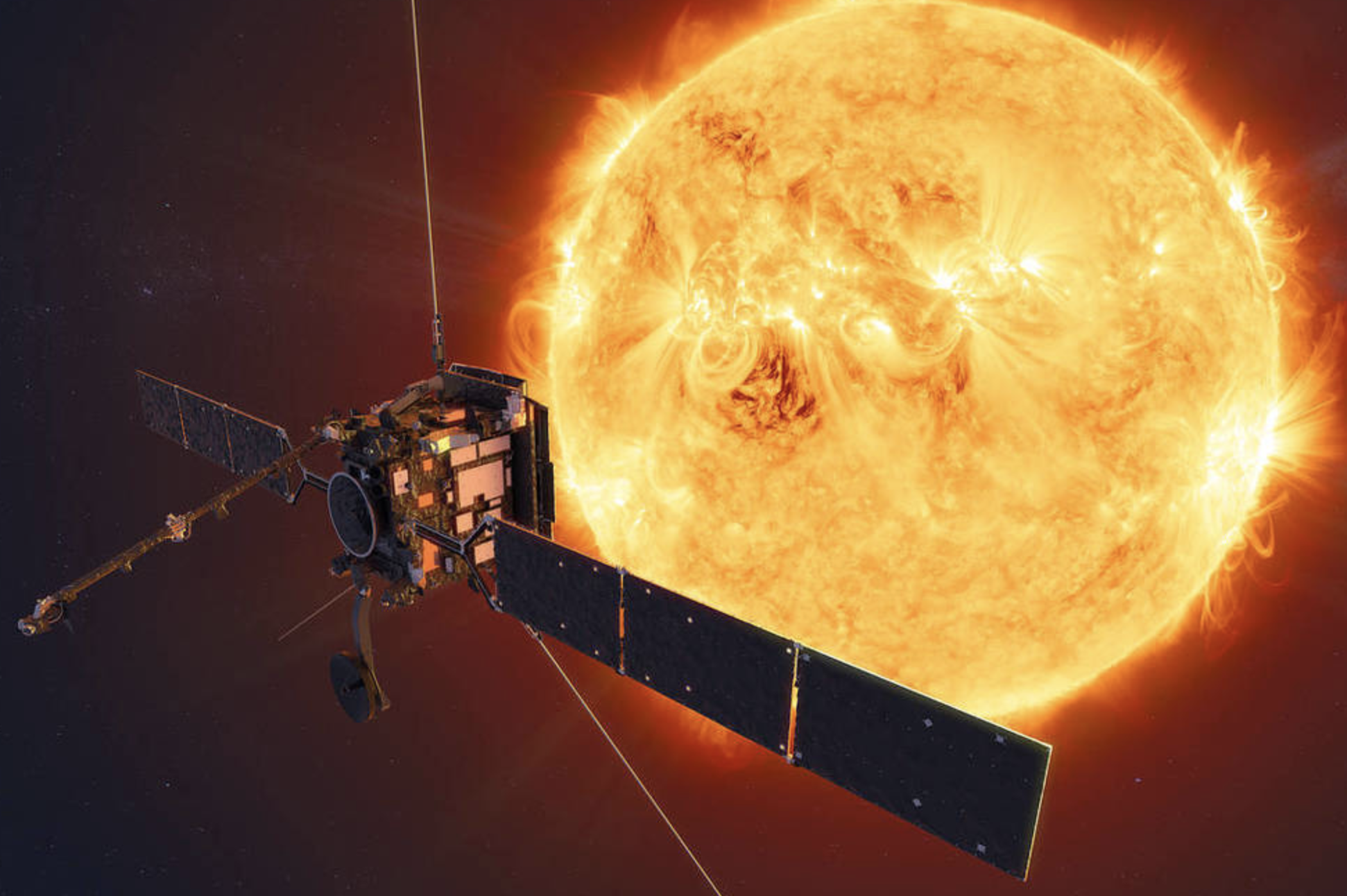

The Solar Orbiter mission has captured the highest-resolution images of the sun’s surface, offering unprecedented insights into the dynamics of our star. These stunning visuals reveal intricate details of sunspots, plasma movements, and the magnetic fields that govern solar activity, providing scientists with valuable data to further understand solar phenomena.

The images, taken on March 22, 2023, and released this week, were captured using the spacecraft’s Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) and Polarimetric and Helioseismic Imager (PHI). Positioned 46 million miles from the sun, the Solar Orbiter, a joint mission by the European Space Agency (ESA) and NASA, captured these extraordinary views, marking a significant leap in heliophysics research.

Cutting-Edge Observations

The Solar Orbiter’s PHI instrument produced the sharpest full-surface views of the sun’s photosphere, where temperatures range between 8,132°F and 10,832°F (4,500°C and 6,000°C). These images reveal sunspots, dark regions caused by the sun’s strong magnetic fields, which disrupt convection and make the spots cooler and darker than their surroundings.

The PHI also created detailed magnetic maps, or magnetograms, showing magnetic field concentrations in sunspot areas. A velocity map, or tachogram, highlighted the speed and direction of plasma flows across the surface, with blue regions indicating movement toward the spacecraft and red regions moving away.

Meanwhile, the EUI focused on the sun’s corona, its outermost atmosphere, where temperatures soar to 1.8 million degrees Fahrenheit (1 million degrees Celsius). The corona’s glowing plasma structures, protruding from sunspot regions, were vividly captured, helping scientists probe why this layer is significantly hotter than the surface below.

Each image released by the Solar Orbiter is a mosaic of 25 individual shots, meticulously pieced together due to the spacecraft’s need to rotate while capturing the sun’s entire face.

Complementing Parker Solar Probe

While NASA’s Parker Solar Probe will soon make its closest approach to the sun, coming within 3.86 million miles on December 24, its mission lacks imaging capabilities due to its proximity to extreme heat. Solar Orbiter’s imaging instruments, however, are filling this gap, offering complementary data for scientists studying the sun’s magnetic field, solar winds, and other phenomena.

“The closer we look, the more we see,” said Mark Miesch, a NOAA scientist. “These high-resolution images bring us closer to understanding the sun’s intricate interplay of magnetic fields and plasma flows.”

Solar Activity Peaks

Solar Orbiter’s observations come at an opportune time, as the sun has reached its solar maximum — the peak of activity in its 11-year cycle. During this phase, sunspots proliferate, magnetic poles flip, and solar activity increases, generating phenomena such as flares and coronal mass ejections (CMEs). These events produce space weather that can affect Earth’s power grids, satellites, and communication systems.

The sun’s heightened activity also creates spectacular auroras, with charged particles from CMEs interacting with Earth’s atmosphere to produce the northern and southern lights.

Solar Orbiter’s mission aligns with this dynamic period, allowing scientists to correlate its high-resolution imagery with real-time solar activity.

Paving the Way for Solar Science

With its groundbreaking instruments, Solar Orbiter is helping answer fundamental questions about the sun, such as the origin of solar winds and the reason behind the corona’s extreme temperatures. Together with the Parker Solar Probe, these missions are reshaping our understanding of the sun’s impact on the solar system and Earth.